By: Meghan Yuri Young Photography: Max Power Conductor Daniel Bartholomew-Poyser has made a career out of pushing orchestral music’s boundaries. As the Toronto Symphony Orchestra’s principal education conductor and community ambassador, he’s envisioning shows where…

By NowPlayingToronto

By: Meghan Yuri Young

Photography: Max Power

In Daniel Bartholomew-Poyser’s world, disruption isn’t just a concept happening in the digital space or in the economy. It also extends to classical music. That’s because Daniel — who is the Barrett Principal Education Conductor and Community Ambassador for the Toronto Symphony Orchestra (TSO) — has spent his career challenging institutional norms to bring the musical genre to the masses.

His own feelings of being “othered”, as he struggled with his sexuality for many years, and desire to connect with various communities, have inspired Daniel to conceptualize shows for audience members who may feel unwelcome in traditional spaces. Daniel’s concerts have reached populations as diverse as the LGBTQ2SI+ community, neurodiverse people (including patrons on the autism spectrum), imprisoned individuals, and many others. The inclusive approach even propelled him into superstardom when CBC detailed Daniel’s story as a gay, Black conductor in the 2019 award-winning documentary, Disruptor Conductor.

Today, as he leads the TSO’s community outreach and educational efforts, Daniel is continuing to use his talent, passion, and expertise to create access — one symphony at a time.

Meghan Yuri Young: Daniel, you’ve done so much in your career and many people are familiar with you. For those who aren’t, can you introduce yourself?

Daniel Bartholomew-Poyser: Of course! I’m an orchestral conductor, and I’m also an educator, arts innovator, entertainer, music historian, and a speaker. I am a lot of different things that all come together under the roof of “conductor”. As to what I do, I basically go to an orchestra, learn about their community, and then think about the sorts of events that might be relevant and meaningful to that community within a city.

MYY: I think that, for some of us, what a conductor does is a bit mysterious. Can you offer some more insight?

MYY: I think that, for some of us, what a conductor does is a bit mysterious. Can you offer some more insight?

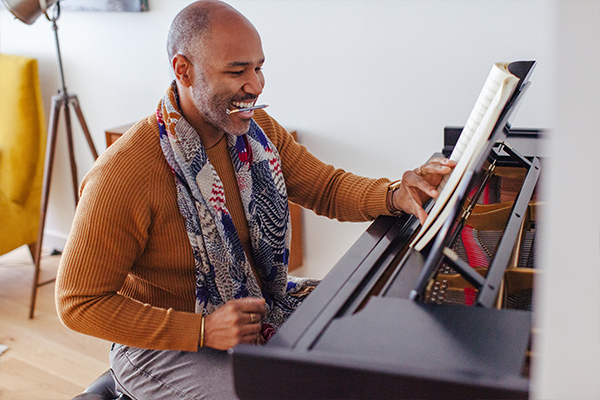

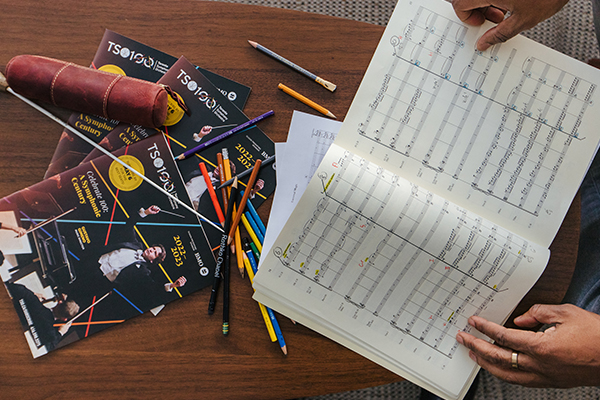

DBP: What I initially described is the end product of what a conductor does. I think what a conductor actually does is, imagine. [They] imagine what notes on a page are supposed to sound like; how the composer wanted these notes to sound; what these notes could sound like with this particular orchestra. What could it sound like given a little bit more French horn there, or a little bit less violin here, or a little bit more tuba, or a little bit more harp? How could it sound in the context of an education concert, or a masterworks concert, or an outreach, or in a particular community? It’s also imagining how people will react, how people will receive it, and how the musicians will feel playing the music in a certain order.

Then it’s making sure you have a vision for what everything can be for people who are coming that night; that the musicians are aware of what the vision is and getting them all on the same page; and removing all the obstacles in their way to play their best. Once you’ve given them the vision, they go off and run with it to create an impact on the audience.

A lot of [a conductor’s job] is actually studying music. In fact, you’re usually fighting, fighting, fighting to clear time in your day to study the music. That’s where it all comes from.

MYY: I never thought of it that way! You are the thread that holds everything together.

DBP: Yes, and what I described is all behind the scenes. In the actual moment, it’s like live project management in a concert. Physically, I’m dividing the time. The music is arranged in time. A conductor is giving indications as to what happens all the way along. The conductor’s body is a text that the musicians need to be able to look up at in a glance to get all the information that they need with regards to tempo, expression, tone. It’s all about time.

MYY: Can you share your journey to becoming a conductor?

DBP: It started with playing instruments, first piano and then tuba. Tuba was the first instrument that I studied in a junior high school band program, like a lot of young people do. Then I picked up the cello along the way. But I knew from around age 13 that I wanted to be a conductor, and it was quite a journey from there to actually becoming one. It’s hard to become a conductor. It’s hard to stay a conductor as well.

MYY: I know you were actually a teacher before you became a conductor. Why is it so hard to become one and maintain the role?

MYY: I know you were actually a teacher before you became a conductor. Why is it so hard to become one and maintain the role?

DBP: It’s really competitive, and it takes time to build trust. It’s really about the orchestras trusting you as a musician, trusting your consistency, and trusting your reliability. On top of that, a conductor has a peculiar difficulty of being exposed to so many different historical opinions about how things should go. You just hope that, over time, your interpretations and way of working has a basic quality to it that has people wanting to continue working with you.

[American conductor] Edwin Outwater, who’s one of my mentors, says, “Nobody has the right to conduct. You’re invited to conduct. You’re asked to conduct. You can’t say, ‘I deserve to conduct.’ You’re there because somebody has asked you to be there; because somebody has put you there.” You have to respect that. You don’t just get to do this. It’s a big honour. It’s a big responsibility.

MYY: That was very insightful for anyone looking at alternative music industry careers! You’re originally from Calgary, and you’ve worked with orchestras in numerous Canadian cities such as Thunder Bay, Kitchener, and Halifax. Tell me about how those experiences shaped your career.

DBP: I was actually born in Montreal and raised in Calgary. [Over the years,] I did the best I could in my roles, hoping eventually people will notice. You just keep putting stuff out there.

I think one of the big breaks happened when CBC did a documentary on me called Disruptor Conductor. That really boosted my profile. What was special about that documentary, it was about things I was already doing: concerts for people on the autism spectrum, 2SLGBTQ+ concerts with [drag queen] Thorgy Thor, concerts for people in prison, infusing music of Africa into concerts.

Halifax, [for example], is a place where I had basically 100 percent creative control over the concerts I was doing. It’s really empowering when your boss comes to you and asks, “What do you wanna do?” And you’re like, “I wanna do this crazy thing.” And they say, “Okay, I love it.” And then they just leave you to do it. More than that, after it’s done, they come back and say, “That was great. What do you wanna do next?”

Interestingly, being part of the CBC documentary taught me a lot too, and it resulted in a new innovative concert in Toronto. It was a documentary-style concert for young people called Moments, where three musicians performed a difficult solo in front of an audience. But before they did that, there was a three-minute documentary on what it took for them to master that piece and be there on that stage in that moment.

MYY: I’m fascinated with how you’ve incorporated community into your work. How did you decide to be a disruptor in this space?

MYY: I’m fascinated with how you’ve incorporated community into your work. How did you decide to be a disruptor in this space?

DBP: People are more important than music. Music is for the people, not the other way around. We’re not coming to Roy Thomson Hall to worship the orchestra, or the composer, or the conductor. The orchestra and the composer and the conductor are for the audience. We’re supposed to be there for you. I think we need to be reminded sometimes, especially me. In my mind, I’m just like, “I have to do this and I have to do this perfectly.” It actually makes me feel better when I realize I’m here to serve the audience.

There’s a bigger picture and there’s intention. If you don’t have a degree of excellence, you won’t achieve that bigger picture. So, the two are held in tension. It’s not one or the other. We need tools to be able to help musicians, especially younger musicians, navigate that tension between performance and impact.

MYY: You’ve been in many different spaces and places. What are you bringing to Toronto?

DBP: For example, [we held] an education concert for students with Halifax-based reggae singer Jah’Mila. [We have gone] out to Brampton, where there’s a huge Caribbean diaspora. We’re gonna do an education concert that features music of South Asia quite prominently. Imagine Punjabi music with orchestral instruments. We’re working on bringing a children’s book, written specifically for the TSO, to life. We’ll also be partnering with Red Sky [a leading company of contemporary Indigenous performance] again to tell stories from this land.

MYY: It feels like these are just a few examples of how you’re continuing to reach new audiences and keep classical music alive.

DBP: Well, that’s the thing. At no point am I trying to keep anything alive. I don’t think classical is dying. On a recent flight, I watched [the Marvel movie] Thor. The entire way through the movie, it’s all orchestra. Look at what Beyonce did with [her album] Lemonade. It has so many Tchaikovsky notes in it. So, I guess this is one thing I have to push back against. Every 10 years, it’s like, “Orchestras are dying.” Every 10 years, the reason changes. It’s not dying, it’s not gonna die. It’s not gonna go anywhere because the instruments sound really good.

What we’re doing with our offerings, I think of Toyota, which has gone from selling cars like sedans and wagons to five different sizes of SUV and bigger cars. How many different types of cars does a manufacturer have to sell to reach the entire population? That’s how I see our programming. We’re simply creating different models to reach a larger population because, well, why not?

MYY: That analogy is brilliant. It really reframes the idea of trying new things, not to be gimmicky or oversaturated, but because there is something for everyone. What is your bucket list concert for the Toronto Symphony Orchestra?

MYY: That analogy is brilliant. It really reframes the idea of trying new things, not to be gimmicky or oversaturated, but because there is something for everyone. What is your bucket list concert for the Toronto Symphony Orchestra?

DBP: Probably Derrick Skye’s Flames Nurtured the Rose then Brahms’ Violin Concerto.

MYY: Do you have any Toronto artists and experiences you’re into right now?

DBP: One of my favourite composers in the city is Cris Derksen, who’s a two-spirited Indigenous composer. As for experiences, I really love the Distillery District. I love walking on Queen Street. I love the Harbourfront. I love Wards Island and Kensington Market. I like the subway a lot. I like just going on the subway. It’s really clean, and this is really silly, but I love how the train is long and you can look right down the centre to the other end as it goes around a corner. I never get tired of that.

MYY: Is there anything that surprised you about Toronto when you first started exploring?

DBP: How great the transit system was. Compared to a lot of other places, the transit system is really good.

MYY: You’re hopping on the subway, what is your perfect night outside of Roy Thomson Hall?

DBP: Definitely dinner and a show. I’d go to Soulpepper Theater in the Distillery and then go to a nearby speakeasy that I don’t want to give away. It’s on King Street, and you have to give a code to get in. It’s really cool.

To witness how Daniel Bartholomew-Poyser is helping to ensure the Toronto Symphony Orchestra reflects Toronto, check out its current offerings. Learn more about one of Daniel’s favourite spots in Toronto, The Distillery District, in our blog about experiencing the city during warmer weather.